By Matt Patches on

“There wasn't anything special about it.”

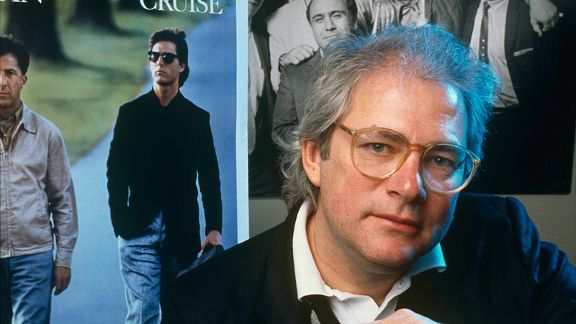

That's producer Mark Johnson on Rain Man, his sixth collaboration with writer-director Barry Levinson. But Johnson wasn't quite right. Twenty-five years ago, Rain Man — a talky drama about two very different brothers on a road trip — won the Academy Award for Best Picture and soon became the highest-grossing movie released in 1988.

“[During the filming] I remember a few crew members came to me after a particularly poignant scene and they said, 'This film is going to win an Oscar,'" Johnson recalls. "And I said, 'What? I'm just hoping it goes through the gate.'"

Rain Man’s gargantuan success erupted from a languescent industry to become one of the most incredible success stories of its era. How did it happen?

The movie's domination of the American box office would have been believable in the 1970s, when small, personal dramas like Love Story and Kramer vs. Kramer climbed to no. 1 with the same momentum as Star Wars and Jaws. But Rain Man arrived on December 16, 1988, on the heels of Die Hard and Who Framed Roger Rabbit and just before Tim Burton's Batman and the highly anticipated sequels to Lethal Weapon, Back to the Future, and Ghostbusters. It was a time when Hollywood was just beginning to perfect its blockbuster science. For its part, Rain Man didn't even manage a no. 1 opening; its $7 million take was topped by the second week of Arnold Schwarzenegger's Twins. Flash forward to hundreds of millions of dollars and an armful of gold statues: Rain Manfinally exited the box office top 10 after the weekend of May 26, 1989, as Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade seized control of multiplexes. The movie's final domestic tally: $172.8 million.

No one in their right mind would green-light Rain Man today. Levinson, whose most recent films include the found-footage horror movie The Bay and HBO's Phil Spector, can't help but agree. “A movie about people … I'm not sure you would even get distribution," Levinson says. "And if you had distribution, they would put a toe in the water and hope they got some money back. Break even and call it a day. It's the nature of the business today.”

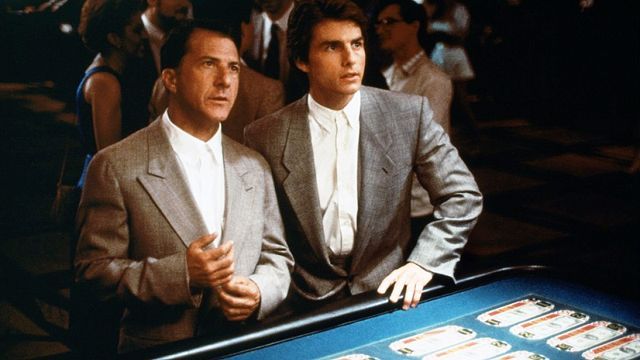

At a budget of $25 million, it would fall right into Hollywood's blind spot: too expensive for a character-driven, “indie-minded” picture and too small-scope to throw money at. (Today's “safe” prestige bet is more like August: Osage County, a Pulitzer Prize winner with 18 speaking parts primed for A-list stars.) There wasn't a target demographic for Rain Man, nor a case study that could predict it would become a massive hit. Even the pairing of Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman, two of the biggest stars on the planet, would demand a higher concept. Unless Raymond the autistic savant was the key to protecting Earth from time-traveling space monsters, there's little chance that pairing would be worth the gamble. And yet, Rain Man was green-lit, untouched by the plague that runs rampant through the industry: overthinking.

Levinson and Johnson were fresh-faced guns for hire when they first met on 1977’s High Anxiety. Levinson was one of the four writers who assisted Mel Brooks on set, throwing out performance notes whenever the director was in front of the camera. Johnson, the second assistant director, quickly bonded with Levinson. When the opportunity emerged for Levinson to start writing and directing his own pictures, he chose Johnson to be his producer. A lack of experience and clout wasn't important; Levinson wanted someone who was going to be around all the time to fight for the movies he wanted to make.

“We did Diner at MGM at a time when they didn't expect much from Diner,” Johnson says of their first endeavor. “But all their money was tied up in things like Cannery Row, or there was a Robert Altman women wrestling movie — a couple of things that didn't pan out. And Diner was a movie that could.”

Originally, the two were set to film a version of Toys, the Robin Williams fantasy-comedy that they eventually made in 1992. It didn't happen right away. Putting the kibosh on a grittier version of Toys wasn't a death knell for the project like it might be today; although 20th Century Fox president Sherry Lansing wanted the movie to get made, juggling other projects forced Levinson and Johnson's debut into turnaround. So they picked up their checks for Toys — Johnson received $75,000 just for developing the movie — and headed to MGM to produce Diner in 1982.

Today's directors are easily pigeonholed. Make a successful horror movie, make eight more just like it. Knock a stunt-heavy action flick out of the park and prepare for two more installments and a lifetime of knock-offs. It's the easiest way to turn movies into products. In the early '80s, when studios were still hungry for great stories and star vehicles, there was greater flexibility. Levinson and Johnson took full advantage: AfterDiner came the baseball movie The Natural (1984), the F/X-heavy Young Sherlock Holmes (1985), the personal Tin Men (1987), and Good Morning, Vietnam (1987).

Rain Man was already a remnant of the past by the time Levinson stumbled upon it. Written by Barry Morrow (and later rewritten by Ronald Bass), the script throws two vivid characters into the road movie blueprint: Charlie (played by Cruise), a hot-shot car dealer, and his autistic brother, Raymond (played by Hoffman), who demonstrates savant-like observational skills. The film was inspired by Kim Peek, whom Morrow met in 1984 while researching a film on the mentally challenged. Though Peek wasn't autistic, he did possess a seemingly superhuman memory, and the encounter sent Morrow to work.

Morrow established the film at MGM in the mid-'80s before handing it off to a number of filmmakers for further development (Gardens of Stone screenwriter Bass was eventually hired to rewrite the script). Scent of a Woman director Martin Brest, Steven Spielberg, and Sydney Pollack all flirted with the project before withdrawing. Johnson credits CAA agent Mike Ovitz (who later became president of Walt Disney Pictures) for keeping the film afloat. Ovitz held tight to the idea of casting Hoffman and Cruise — though early in the script's life, it was thought that Hoffman would take the Charlie role opposite Bill Murray as Raymond.

When Levinson and Johnson arrived at the project, Rain Man was getting bloated. Dropping Charlie and Raymond on the road together wasn't enough — there was an inkling to go bigger, to be flashier, to overload.

“Both Steven Spielberg and Sydney Pollack gave Barry credit for trusting the material,” says Johnson. “There are drafts where a lot more happened. The brothers are chased by a motorcycle gang and Raymond figures out how to put together a motorcycle and they run away. Plot points. Barry said no. 'This is two schmucks in a car.' He trusted the duo.”

Rain Man was not a zeitgeist movie, nor was it intrinsically “awards-friendly.” To this day, Johnson says he has never entered a pitch meeting and talked up Oscar potential, though he's sure it happens. By 1988, MGM just wanted Rain Man in the can and ready for the Christmas season. Levinson rehired Bass, and together they stripped it down to a bare-bones character piece. Or they tried. As Levinson, Johnson, and their crew prepared to shoot Rain Man, the 1988 writers' strike went into motion. “We had a partial draft,” recalls Levinson. “We didn't finish it at the time. We were saying, 'We have to start.'” And so they did. That meant no rewrites, no tinkering during production.

The catastrophe was bittersweet. It's a completely foreign notion today: Levinson made the movie he wanted to make. With MGM forced to trust the director to finish it, Levinson set out to shoot Rain Man with a road movie framework and an open mind. “The key to the whole movie was that it was shot in continuity. You start seeing certain things, seeing the relationship, and start adding things here and there," Levinson says. "It starts to click.”

The script originally saw Raymond and Charlie coasting along the highway toward Los Angeles — a straight shot. It dawned on Levinson that the monotony of the road might be … really boring. “Someone said, 'Well, it's the fastest way to get to L.A.' I knew that, but we had to figure something out,” he says. “But what if there's an accident on the highway? Then he doesn't need to stay on the highway. And then there are all these statistics about accidents on the highways and he's disturbed by that. His issues could prevent him from going on the highway. So we got a better look for the movie while reinforcing his behavior.'”

Knowing the script could be continually tweaked on the fly allowed Levinson to approach it like a member of the audience. Questions were always being asked, character motivations considered. Levinson wondered, Why doesn't Charlie send him back to the institution? and the production was flexible enough to allow for a new scene that showed Raymond as a potential danger to himself (it involved waffles, an oven, and the near-burning-down of a house).

“In many ways, it was the most independent movie that you could possibly make,” says Levinson. “So much of it was being discovered on the road.” According to the director, MGM let the production proceed without interference. Levinson never looked back, either.

After wrapping the film, Johnson wasn't convinced they had anything resembling a hit on their hands. He recalls watching a rough cut with Levinson and editor Stu Linder. “I thought [there was] a lot of work to be done,” he says.

But prerelease buzz was positive. “I think we were rewarded for the boldness of casting Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman as brothers,” Johnson says. “It was one of those combinations where one and one really adds up to three.”

Talk of star turns and awards prospects created an echo chamber. “I remember going to the British premiere and someone yelled when the lights came up, as Dustin and Tom were walking out of the theater, 'You both deserve an Oscar!'" Johnson says. "I heard for weeks and weeks that we had it in the bag."

The struggle of producing modestly budgeted pictures in today's landscape boils down to marketing dollars. A movie may only cost $30 million, but it takes another $30 million to properly sell it. But according to Johnson, the studios employed the same model in 1988. He estimates that with marketing costs, Rain Man was likely a $50 million investment.

That Rain Man failed to open at no. 1 in America was not a cause for alarm. There were fewer theaters, and they were willing to run films for longer periods of time. The same movies might reside in a theater for several months at a time. Couple that with the way box-office numbers were crunched back then: in Variety and in few other places. No one in Ohio was turning on their local news to see that Rain Man had missed the mark in its opening weekend. Johnson compares the experience to the recent 47 Ronin, a blockbuster whose backstory predestined it to fail, saying the disappointing box-office numbers have been overscrutinized by the media. No one kicked Rain Man to the ground when it opened at no. 2 — the weeks ahead were competition-free (how many people remember DeepStar Six?). Rain Man took the no. 1 spot after its second week of release and remained there for the entire month of January 1989.

Rain Man effortlessly achieved four-quadrant — the industry term for demographically universal — success, despite mixed reviews. Legendary New Yorker critic Pauline Kael notoriously battered the movie into a bloody pulp, calling it “wet kitsch” and writing of its lead performer, “Dustin Hoffman hump[s] one note on a piano for two hours and eleven minutes.” But Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel praised Hoffman and Cruise with two thumbs up. Rain Man became classic watercooler fodder, raising awareness and curiosity about autism while taking flak for inaccurately portraying the disorder. Still, audiences flocked, including the discarded demographic: women. The Los Angeles Times reported in February 1989 that MGM/UA research studies found that the film's average audience was 55 percent female and 45 percent male, with two-thirds of the audience over the age of 25.Rain Man was a movie for everyone made for no one in particular.

Rain Man was also a global success, earning more than $182 million in foreign markets (according to Levinson, there was even a dream weekend when the film topped the box office in each country it was playing in, like stars aligning). To this day, the director is somewhat baffled by the universal appeal of Rain Man. During the press tour, he and Hoffman visited Japan and were met with raving fans. “It was huge. Huge,” he says. “It seemed to capture an emotional quality they were able to relate to.”

“Everyone was talking about it," says Johnson. "It was unnerving.” The love for Rain Manrippled out of Los Angeles and New York, as did prognostication of the film's Academy Awards potential. Rain Man dipped to the fourth spot at the box office by February 1989 just as MGM upped its Oscar-themed advertising. On February 15, the day of the nominations announcement, the studio beat the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences to the punch by printing an ad in newspapers touting Rain Man as an Academy Award nominee. The move prompted an investigation of potential foul play, but MGM representatives brushed off the accusations. They knew they had a sure thing.

The 61st Academy Awards aired on March 29, 1989. Rain Man was nominated for eight awards. After a dizzying run, it only hit Johnson that he had an Oscar-nominated film on his hands while sitting in the audience, waiting for the winners to be announced. “I was sitting next to my good friend Robin Williams and he claims my fingers went through the armrest of the chair because I was so nervous,” he says. “I'm sure I was no fun to be around. Everyone said we were going to win, but there was a point where I thought, But what if we don't?”

Johnson had little to worry about. Rain Man triumphed, taking home four statuettes: Best Screenplay, Best Actor, Best Director, and Best Picture. The following weekend, its 16th in theaters, the movie shot back to no. 1.

Johnson went on to produce a broad range of projects, including the Chronicles of Narniafilms, Breaking Bad, Galaxy Quest, and Lance Hammer's self-distributed drama Ballast. But looking back, he says a studio wouldn't produce Rain Man today. It wouldn't play to a broad enough audience, they'd say. The historical data doesn't support its success.

“I go to pitch movies all the time and they say, 'We love you, but know we're not interested in dramas.' If it won't travel, if it's too American, they aren't interested. You point to a movie — 'Look at how Argo did!' — and they'll [just] say it's the exception that proves the rule.”

Making Rain Man — through a writer's strike, and defined by non-commercial subject matter — was not easy. Still, Johnson says it never is.

“A lot of my contemporaries complain that [making movies] is harder than it ever was," he says. "But I maintain that it's always been hard. It's just different.”

No comments:

Post a Comment